You may be familiar with the Cherokee Phoenix newspaper and the closely related Cherokee Advocate, but did you know that Cherokee students in the 19th century also published their own newspapers?

By the time of Cherokee Nation’s forced removal west in the 1830s, education had become an institutionalized part of Cherokee life, thanks to the arrival of missionaries some 45 years earlier. Through the efforts of those missionaries and the successful adoption of Sequoyah’s syllabary system of writing our language, literacy in both Cherokee and English was common throughout the Cherokee Nation by the 1840s. (Check out Cherokee Almanac: Educating A Nation: The Cherokee Public Schools Act – OsiyoTV for more on that!)

Cherokee leadership embraced literacy as a way to level the playing field as Cherokees increasingly dealt with encroachment from the United States. Thus, our education system by the mid-19th century included more than 30 public schools, several missionary schools, and a male and female seminary to provide localized higher education. An orphanage for Cherokee children was added in 1871.

While each school had its unique purpose, all of their students were equally proud of their school’s accomplishments. As a means to demonstrate both scholarship and pride, each published its own newspaper at various times.

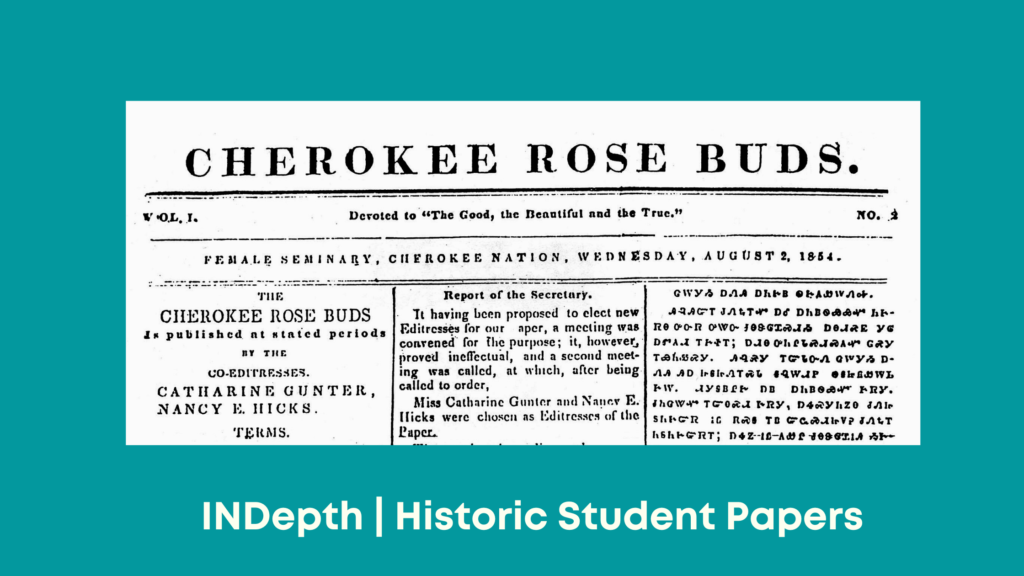

It was the Cherokee National Female Seminary students (Cherokee Almanac: The Cherokee Female Seminary – OsiyoTV) who first debuted their newspaper, A Wreath of Rosebuds, on August 2, 1854, “Devoted to the Good, the Beautiful, and the True.” The young women of the seminary had been nicknamed the Rosebuds, a title they embraced and often cleverly played upon in the paper. Copies sold for 10 cents, and it published twice per year.

Their paper contained thoughtful essays on subjects such as “Beauty” and “Female Influence.” It also offered several articles printed in the Cherokee syllabary. Often the essays seemed intended to convince outside readers of the advancement of the Cherokee people, contrasting life before missionaries and education with the advantages of modern times. Still, the young women remained attuned to their communities and revealed a love of nature and their countrymen in subtle ways.

A particularly poignant note in their August 1855 paper spoke of concerns over a lingering drought that year. Conditions were so bad that a national day of fasting and prayer had been recently observed.

“About 3 o’clock that afternoon the wind began to blow and clouds overspread the firmament, and at night the rain fell copiously. All nature seemed refreshed. Ever since we have had occasionally heavy showers. The farmers think their crops will be bountiful this season; and perhaps they will have more corn than was ever before raised in the nation.”

Not to be outdone, in August of 1855, students of the Cherokee National Male Seminary (Cherokee Almanac: Tribal Intentions of the Cherokee Male Seminary – OsiyoTV) published the first issue of the Sequoyah Memorial. Its masthead touted, “Truth, Justice, Freedom of Speech and Cherokee Improvement.” The students wrote of their daily experiences, shared poetry, expressed their admiration for the young women of the Female Seminary, acknowledged marriages of alumni and made humorous observations. Some wrote essays that dispensed virtuous advice, such as “The Value of an Unspotted Reputation” and “Laziness, the Road to Misery.” Occasionally a joke was inserted (Why is a good musician like a clock? Because he keeps time.) Among its first editors was one Joel B. Mayes, who would later be elected Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation.

At the close of the U.S. Civil War, which spilled over into Cherokee Nation, many Cherokee children were left homeless and orphaned. Where previously the rare orphaned child was boarded and cared for at one of the public schools, the post-Civil War numbers were too great to accommodate that. The Cherokee Nation opened an “orphan asylum” near Salina, Indian Territory, to provide a home and education for such children. (Cherokee Almanac: The Cherokee Orphan Asylum – OsiyoTV)

The orphanage spawned two newspapers, the Cherokee Orphan Asylum Press and a supplement called the Children’s Playground. While the Orphan Asylum Press was published weekly by the school’s superintendent, Rev. Walter Adair Duncan, the Children’s Playground came from the students themselves. The former could be counted on for more serious news and opinions about the Cherokee Nation, including election results. But the Playground was different. The students’ grades were posted. In its pages the orphans shared their thoughts and observations about school life and each other, while learning a practical skill – typesetting.

The Playground’s masthead motto was, “A little nonsense now and then is relished by the best of men,” although clearly not everyone thought nonsense was a good idea.

“We can always tell a person who minds his own business, he is slow to speak and quick to hear. Often, we should have better lessons in school, if we minded our lessons and spent no time looking around to see what others were doing. Examinations will soon be here then people can see whether WE have been minding our business,” wrote editor Lizzie Stinson tartly.

With statehood and sometimes fire forcing the closure of these tribal institutions (the orphanage burned down in 1903), the presses for such school newspapers ceased to run. Today we can be grateful for these archived publications, giving us a glimpse into the lives of young Cherokees from earlier generations.